Understanding Self-sabotage Through the Window of Tolerance

Self-sabotage can even occur to relieve strugglers from the distress of wellness.

addiction is . . . deeply rooted in the neurobiology and psychology of emotions.

Gabor Maté, MD, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts

Self-sabotage is an act of impeding one’s own progress in recovery, possibly risking relapse. This can bewilder witnesses because it often lacks any rational explanation. To understand why we get in the way of ourselves, we need to cover a topic I’ve been meaning to write about: the window of tolerance.

Dr. Dan Siegel coined the term in 1999 to describe the optimal zone of nervous system regulation in which a person can function effectively. Another way of saying it, the window is your emotional comfort zone. Exceeding one’s emotional limits can lead to overreactions or shut downs.

When was the last time a discussion with your partner became an argument? An overreaction to something your partner said, or vice versa, illustrates how being triggered is a response to shifting outside one’s tolerable level of emotions.

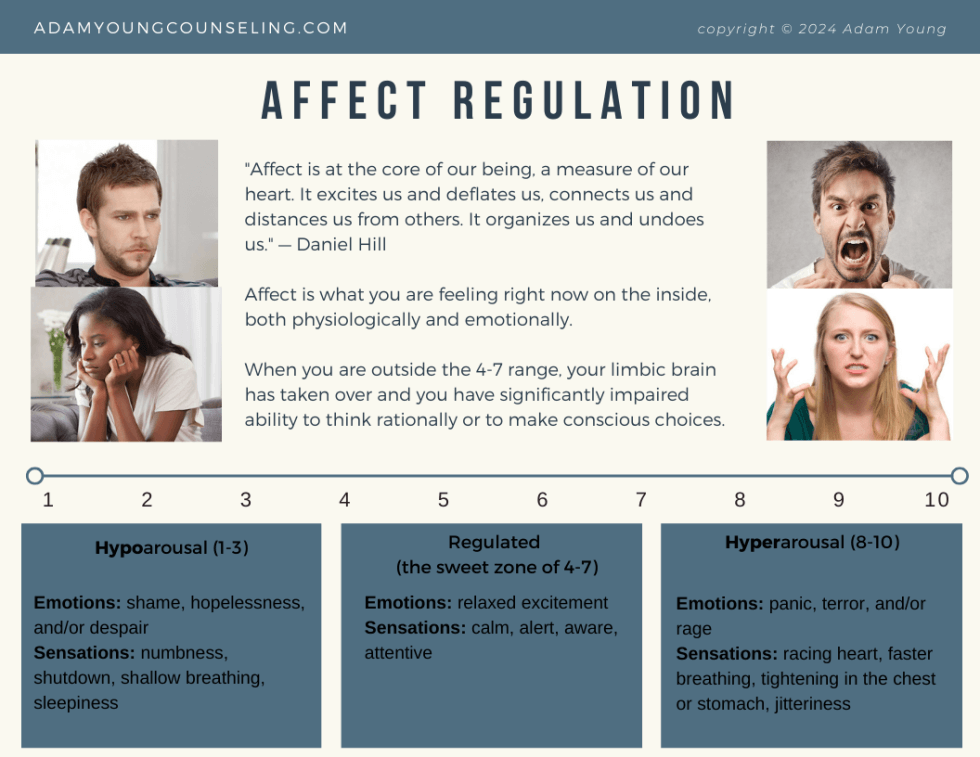

I like to think of the window along a scale. Adam Young, host of The Place We Find Ourselves podcast, offers this visual aid below as a reference. He calls it “affect” regulation. He and Dr. Siegel are referencing the same thing: the nervous system response to stimuli.

If affect regulation is a new concept for you, Adam explains it well in Episode 20 of his podcast. He also states, “All addictions and compulsions are, at their core, attempts at affect regulation.” Which of course is the point of this article and the cornerstone of our recovery practice.

Why is this relevant to strugglers? Because addiction is a pattern of outsourcing to relieve internal dysregulation. That’s why attempts at controlling behaviors is short-lived. We have to address the inner source for long-term recovery.

Let’s examine Adam’s scale if the window of tolerance is a new concept for you. Hypoarousal and hyperarousal are the extreme ranges of reactivity. Hypo, meaning under, is represented by states of degree in sadness or despair. Alternatively, hyper, meaning over, represents states of degree in extreme fear or anger. A well-regulated zone of peace and calm is in the middle.

I listen to others describe the middle (regulated) zone of the window of tolerance as the ideal state. And, the wider the window, the more one can sustain greater degrees of stress before reacting to it. While that’s true, I share my observations differently.

I find that a struggler’s window is generally centered on one end of the scale rather than in the middle. It’s a spot that feels familiar, endurable, and possibly comfortable. It’s suitable because this is where they have learned to adapt and operate in their environment. Sometimes, to survive.

I find that a struggler’s window is generally centered on one end of the scale . . . this is where they have learned to adapt and operate in their environment.

Before my recovery, my normative emotional state centered in the 8-9 zone. My family said living with me felt like walking on eggshells. I described it as a teapot at near-boil. It didn’t take much to set me off. I would vent some steam (unable to contain anger) and then return back to alert agitation.

It’s no coincidence that I had trouble relaxing. Joy was out of the question. So my narrow window of tolerance that centered in the 8-9 zone could neither bear a higher level of stress (10 zone) nor lower levels of calm (7 or lower). The 8-9 zone was my norm from where I navigated the world—all day, every day.

My point is, many people cannot tolerate the ideal “regulated” middle zone on the scale. Strugglers and betrayed partners alike have nervous systems centered in a different zone. Self-sabotage can be explained from this perspective.

I mentioned internal dysregulation above. A way of describing “dysregulation” is shifting outside one’s window of tolerance (one’s normative center on the scale). Characteristically, we don’t react quite as well as we would prefer. Self-sabotage has many faces:

Negative self-talk may be attempts to return ourselves to our normative zone.

Keeping ourselves busy may be a distraction from an unbearable zone.

An inconsistent work/life balance may fit comfortably in your zone.

These expressions and behaviors tend to be easily identified by others. What they can’t see—and often missed by oneself—is the distress inside. Emotions are constantly sending signals, but we place ourselves in jeopardy when we’re not self-attuned to those messages.

Strugglers typically miss or dismiss the signs: ambivalence, tension, anxiousness, just to name a few. Emotions try to tell us what we need. When we don’t care for them, the nervous system will take matters into its own hands, figuratively speaking. Compulsion is a search for relief. That’s the outsourcing I mentioned.

Relief from dysregulation may look like bouts of pornography, food cravings, smoking, overworking, seeking validation from others . . . any substance or behavior that one’s nervous system has learned reduces distress.

What surprises many of their loved ones is that this reaction can occur during good times as well as bad. It makes sense that a relapse could occur after a death in the family or being fired from a job. Yet, the well-regulated middle zone does not feel ideal for people whose normative state is centered outside of it.

The well-regulated middle zone does not feel ideal for people whose normative state is centered outside of it.

While strugglers and betrayed partners ought to pursue a normative state in the regulated zone, this is not where they find themselves when beginning recovery. For strugglers, the strongly held belief of “I’m basically a bad, unworthy person” results in consigning themselves to hopelessness in the 1-3 zone, or desperate ventures in the 8-10 zone.

Self-sabotage can even occur to relieve strugglers from the distress of wellness. For them, a prolonged period of time outside of familiarity or safety is dysregulating—even if that time is spent in peace. Because they believe something bad will certainly happen soon. Or, there’s no time to rest because their value is based on performance.

From the outside looking in, self-sabotage is bewildering. From the inside looking out, it’s a desperate attempt to regain a familiar state within their window of tolerance. An essential aspect of addiction recovery and betrayal trauma recovery is learning how to expand one’s window of tolerance after re-centering it to the middle regulated zone.